The music industry is dominated by profit-driven corporations. Social enterprises offer a different model — one where artist welfare and community impact are built into the business structure.

TL;DR

Social enterprises in music prioritise artist welfare, community impact, and fair practices alongside financial sustainability. They prove that music businesses can be profitable without being exploitative. We need more of them to shift industry culture from extractive to supportive.

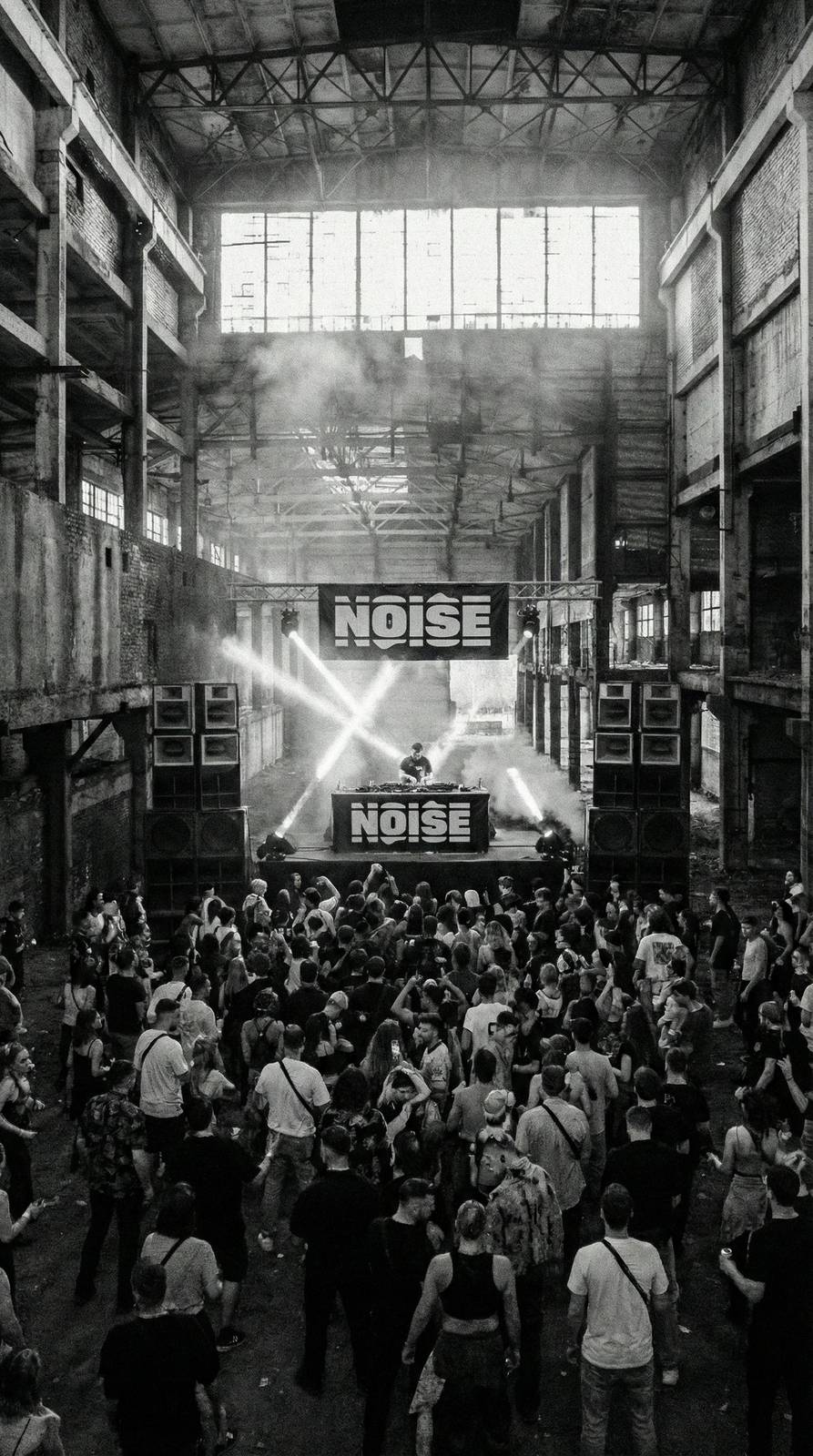

What a Music Social Enterprise Looks Like

A social enterprise is a business that trades to tackle social problems, improve communities, or address market failures. In music, this means organisations that exist primarily to serve artists and communities rather than to maximise shareholder returns. The profit motive exists — sustainability requires revenue — but it's in service of the social mission, not the other way around.

Examples exist across the music ecosystem: community music venues run as cooperatives, record labels structured as artist collectives, music education programmes operated as social enterprises, and platforms (like Noise) that prioritise artist welfare and fair splits as core business principles.

The common thread is alignment between values and business model. A social enterprise doesn't need to choose between doing good and being viable — the doing good IS the business. This alignment produces organisational cultures that are fundamentally different from profit-maximising corporations.

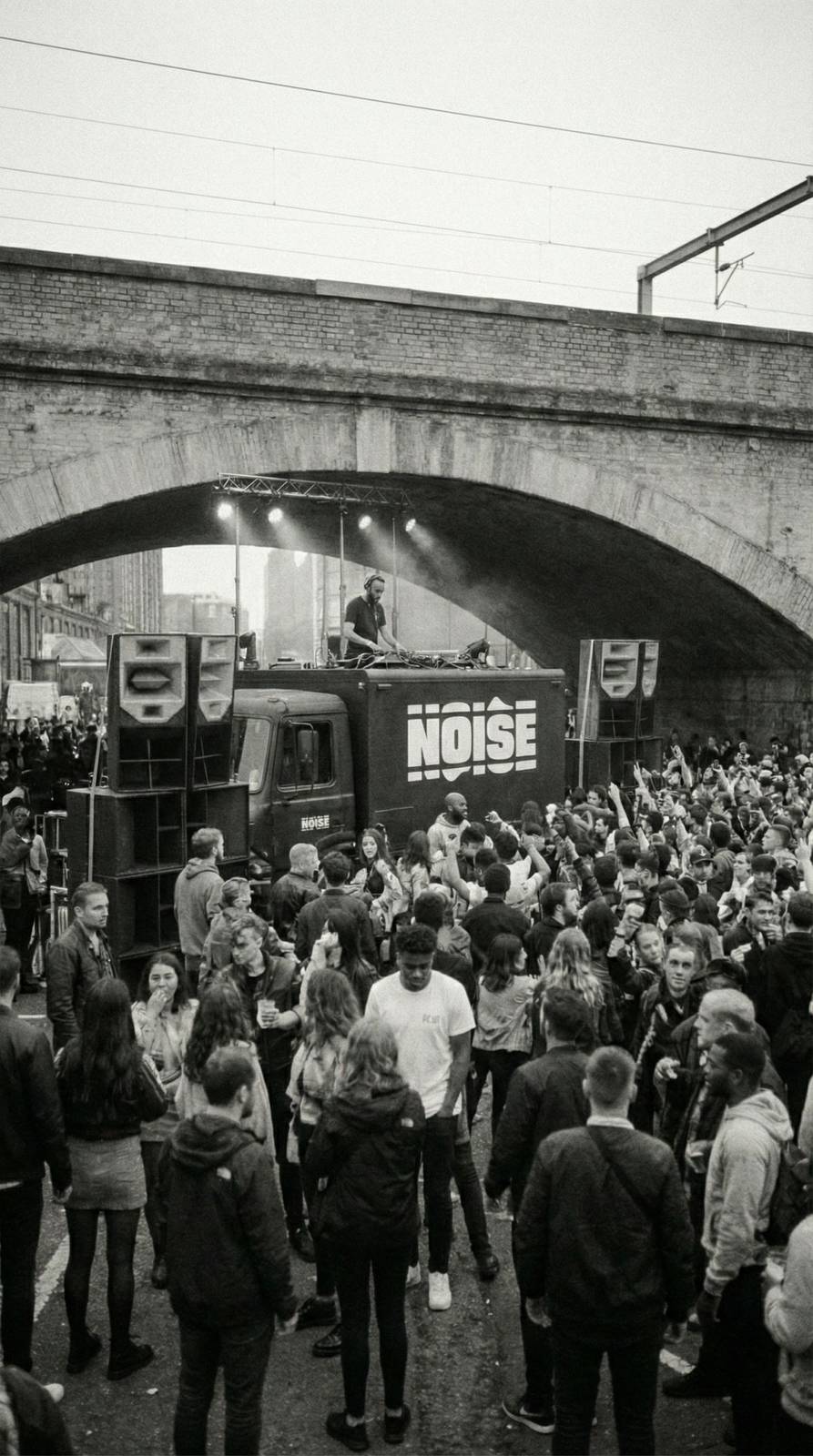

Why the Music Industry Needs This Model

The music industry's dominant model is extractive: identify talent, extract maximum commercial value, move on. This model has produced extraordinary music and enormous wealth — but the wealth concentrates at the top while the artists who generate it often struggle financially.

Social enterprises offer an alternative: a model that creates value and distributes it fairly. Where artist development isn't a cost to be minimised but a mission to be pursued. Where community impact is measured alongside financial return. Where success is defined by how many artists are sustained, not how much revenue is extracted.

The practical benefits are tangible: social enterprises can access funding streams (grants, social investment, community support) unavailable to conventional businesses. They attract talent motivated by values rather than just salary. And they build brand loyalty from audiences who increasingly care about the ethics of the companies they support.

Case Studies That Prove It Works

Rough Trade, while now a commercial entity, began as a cooperative and maintained artist-first principles that shaped indie music culture for decades. Their model of fair deals, creative freedom, and community focus proved commercially viable while profoundly influencing how independent music operates.

Bandcamp (before its acquisition) operated as an artist-first platform that took minimal commission and actively promoted music discovery. Their model demonstrated that technology companies can serve artists rather than exploit them, and their success proved the commercial viability of fairness.

Community-owned venues like Elsewhere in Margate and community-focused organisations like Key Changes (music and mental health) demonstrate that social enterprise models can work at every level of the music ecosystem, from platform to venue to support service.

These aren't niche exceptions — they're proof of concept for an industry that could be structured very differently. Every successful music social enterprise demonstrates that fairness and viability aren't contradictory.

The Challenges and How to Overcome Them

Social enterprises face real challenges: accessing investment (social investors want social return, traditional investors want financial return, and finding capital that satisfies both is difficult), competing with well-funded corporations, and maintaining mission integrity while scaling.

The funding landscape is improving. Social investment funds, Arts Council grants, community share offers, and crowdfunding all provide capital options for mission-driven music businesses. The challenge is navigating these options and building the business case that satisfies both social and financial requirements.

Mission drift — the gradual abandonment of social objectives under commercial pressure — is the existential risk for music social enterprises. Protecting against it requires embedding social purpose into governance structures (community interest company status, cooperative ownership), maintaining transparency with stakeholders, and measuring social impact as rigorously as financial performance.

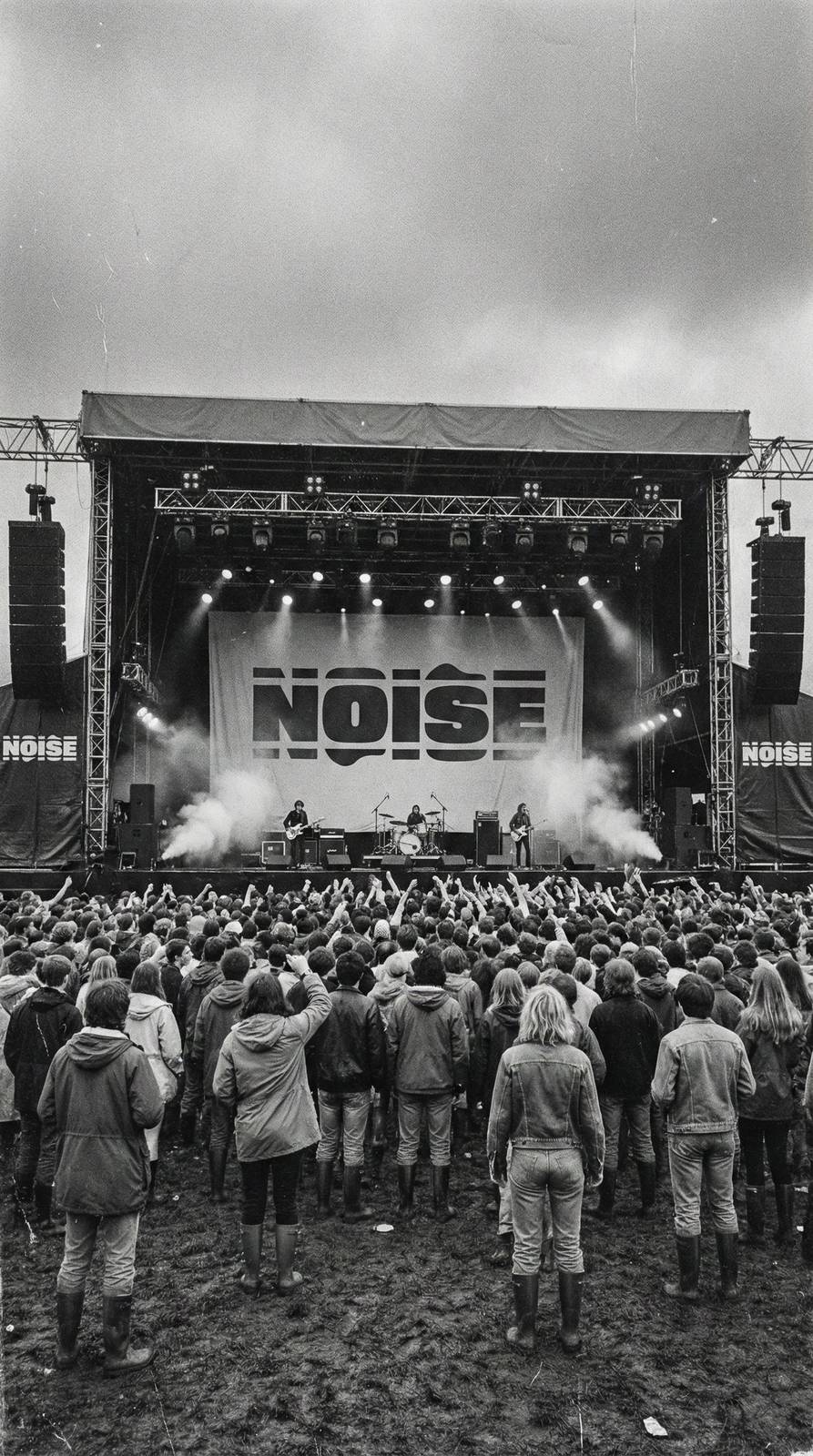

Why Noise Exists as a Social Enterprise

Noise is a social enterprise because we believe the structure of a music business determines its behaviour. A company structured to maximise shareholder returns will inevitably prioritise revenue over artist welfare when the two conflict. A social enterprise structured to serve artists will prioritise artist welfare — because that's literally what it exists to do.

Our model isn't charity — it's sustainable business built on the principle that serving artists well creates commercial success. Fair splits attract better artists. Artist-first values build loyal audiences. Community impact generates brand equity that advertising can't buy.

We need more music businesses built this way. Every social enterprise in the music ecosystem shifts the culture slightly — from extractive toward supportive, from exploitative toward empowering, from corporate toward community. And every shift, however small, moves the industry closer to the one that artists deserve.

If you're thinking about starting a music business, consider the social enterprise model. If you're an artist choosing who to work with, prioritise organisations whose values align with yours. Together, we can build a music industry that works for everyone who makes it beautiful.